Spotting AI-Generated Disinformation and Deepfakes Online

Detecting AI-generated disinformation is an increasingly difficult challenge for individuals, organisations, and society because people rarely recognise how vulnerable they are to influence in the first place, or how easily emotion and bias can be used against them.

Sometimes offence is the best defence, and other times it’s defence that is the best offence, but for Internet users it’s almost always the latter. Yet, an even more effective defence is one that is well-informed. We must understand the threat, the risk it can pose, and which techniques are attempting to be used against us if we are to effectively identify and respond accordingly. Once we understand why and how disinformation and misinformation is affective and how it can be identified, we can put our knowledge into practise.

This piece walks you through the problem by first outlining what the threat looks like, then explaining why it works on us, before examining the psychological exploits attackers rely on. It then moves into practical ways to identify fake content and concludes with a structured process for staying safe online. The aim is to give you both a clear understanding of the threat and practical methods to reduce its impact, supported by a set of recommended online resources in the appendix for those who want to explore further.

Understanding the Threat

AI-generated deepfakes are images, videos or audio recordings that have been manipulated by artificial intelligence to appear authentic.1 In recent years, the volume of social engineering attacks, scams and fabricated media driven by deepfakes has increased significantly, with one analysis reporting a tenfold rise in deepfake related fraud between 2022 and 2023.2 Another study found a remarkable 3,000% increase in attempted deepfake fraud during 2023 alone.3 Both criminal groups and state-aligned threat actors use deepfakes and other AI-generated material to compromise organisational systems, run disinformation campaigns, influence elections, intimidate or blackmail individuals, and commit financial crimes.4 Such content can be highly persuasive, blurring the line between fact and fabrication to the extent that many people struggle to judge what is real.

Furthermore, I often hear the terms misinformation and disinformation used interchangeably, yet they are far from interchangeable, and the difference lies in the intent behind the information.5 Misinformation is false or inaccurate content shared without any intention to deceive, such as someone repeating a business statistic, they heard in passing but misremembered, thinking it was accurate. Whereas, disinformation is false content deliberately created to mislead or manipulate, for example a fabricated health alert posted online to provoke fear and attract clicks.6 All disinformation counts as misinformation, but not all misinformation is disinformation.

Why Deepfakes Fool Us

Humans have an innate tendency to trust their senses, and the saying “seeing is believing” still holds true. Deepfakes exploit this by creating highly convincing fabricated images or video that our brains interpret as genuine, especially when they feature a familiar face or voice.7 We are also inclined to overestimate our ability to recognise fakes and manipulation, with research showing that while many people believe they are skilled at detecting deepfakes and manipulation, their actual accuracy is considerably lower.8 This misplaced confidence can lead us to accept a video as authentic if it simply appears convincing, leaving us more susceptible to sophisticated fakes.

This is reinforced by a 2024 CDC backed meta-analysis, showing that across 56 studies involving more than 86,000 participants, the average human accuracy for identifying deepfakes was only slightly above chance, typically between 57 and 60 percent.9 Even when participants were told that fakes might be present, many still assumed videos were genuine and expressed confidence in incorrect assessments.

To further push this point, Robert Greene, in his book The Laws of Human Nature notes that people tend to overestimate their resistance to emotion, influence and manipulation, believing they can remain rational and objective even in emotionally charged situations.10 In reality, heightened emotions cloud judgement, making individuals more susceptible to manipulation. This is exactly what threat actors exploit. They aim to provoke fear, outrage, urgency or even excitement to bypass critical thinking and trigger impulsive decisions. Deepfakes and AI generated disinformation thrive in these conditions, where overconfidence in your own discernment ironically becomes your own critical vulnerability.

Deepfakes and fabricated news also prey on cognitive biases. Confirmation bias, for example, makes us more likely to believe and share information that aligns with our pre-existing views. If an AI-generated video or headline supports what we want to believe, we are less likely to examine it critically. A viral fake story or video might use alarming material to short circuit rational thinking, prompting people to act on impulse, such as resharing immediately or following urgent instructions, before verifying its authenticity.

It's now a well-established fact that threat actors combine deepfakes with established social engineering techniques. A classic example is from early 2024, where actors used a live deepfake video call to impersonate a company’s CFO, tricking an employee into transferring approximately £20 million GBP to criminals.11 The threat actors relied on the employee’s trust in seeing and hearing her “boss” and created a sense of urgency, which overrode her doubts. Such cases show how deepfakes can strengthen impersonation attacks, making them far more persuasive than a simple phishing email.

Beyond financial fraud and phishing, deepfakes in politics and online media highlight another reason they are effective. People often place more trust in video footage of a public figure than in text, so a falsified clip can be highly persuasive. Research confirms that deepfake videos can influence perceptions of individuals just as strongly as genuine footage, even when viewers are aware that deepfakes exist.12 There is also the problem known as the “liar’s dividend”, as deepfakes become more common, it becomes easier for genuine events to be dismissed as fabricated.13 Powerful figures facing real scandals may claim that video evidence is fake, exploiting public uncertainty. This further obscures the truth, which is exactly the aim of many disinformation campaigns.

The Seven Principles of Influence

As we have discussed, one of the most effective ways disinformation and deepfakes bypass rational thinking, is by exploiting human nature with well-established principles of influence.14 Psychologists have studied these principles for decades, and Dr. Robert Cialdini distilled them into a powerful framework in his influential work Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion.

I like to think of these principles as the “human CVE list”, and our most frequently exploited vulnerabilities:

- Reciprocity

- Commitment and Consistency

- Social Proof

- Authority

- Liking

- Scarcity

- Unity

These principles each deserve their own deep dive, and frankly, reducing Cialdini’s decades of research to a few paragraphs feels criminal. But for the sake of time, here we are. That said, don’t just skim and move on. Actively practicing the skill of spotting these influence tactics in everyday life is one of the most effective ways to build resilience against all forms of social engineering.

Reciprocity: Reciprocity is one of the oldest social rules, rooted in our evolutionary past. Early societies survived by sharing resources, and this instinct still drives us today: when someone helps us, we feel compelled to return the favour. Failing to reciprocate can trigger guilt or social unease, while returning the gesture restores balance and feels rewarding. Such emotions act as social glue, ensuring trust and harmony within groups.15 Even small acts, like a colleague buying you coffee, often spark an urge to repay in kind, this is reciprocity in action.

Commitment and Consistency: Once we make a decision, we strive to remain consistent with it, even when it no longer makes sense. This is driven by cognitive dissonance, which is the discomfort we feel when acting against our stated beliefs.16 Small commitments also pave the way for larger ones, a tactic known as the “foot-in-the-door” effect. When these commitments are made publicly, their influence typically strengthens, as the desire to appear consistent in front of others reinforces follow-through. Consistency signals reliability to others and reinforces our own self-image, making it a powerful lever of influence.

Social Proof: In uncertain situations, we look to others for guidance. If everyone avoids a certain food, we assume it doesn't taste nice; if a crowd queues at one particular food vendor, we assume it’s better. Following the majority feels safer, reduces effort, and taps into our deep instinct that conformity offers protection.17 This tendency is rooted in social learning theory, which highlights how imitation boosts survival by allowing us to learn from others without facing the consequences ourselves.

Authority: From childhood, we are conditioned to trust authority figures. Deference to expertise reduces uncertainty and saves cognitive effort, but it also bypasses critical thinking. The famous Milgram Experiment showed how far people will go when instructed by authority, even against their own judgement. In the study, participants were told by a researcher in a lab coat to administer electric shocks to another person (an actor) whenever they answered questions incorrectly.18 Despite hearing simulated screams of pain, many continued delivering shocks simply because the authority figure insisted.

Liking: We are more easily influenced by people we like. Similarity–attraction theory suggests that shared traits or values foster rapport and trust, making us more receptive to those who reflect ourselves.19 Meanwhile, the halo effect creates a cognitive bias where attractive individuals are perceived as more intelligent, competent, and trustworthy.20 This means that liking someone, because they're similar or pleasing in appearance, can significantly bolster their persuasive influence and our emotional connection.

Scarcity: Scarcity creates urgency. Limited opportunities trigger a fear of loss, which our brains weigh far more heavily than potential gains. This instinct, once vital for survival, now drives consumer behaviour, think “only three left in stock”. Reactance theory explains how perceived restrictions on freedom make those scarce items feel even more desirable, as we push back against being told what we can't have.21 Scarcity also taps into loss aversion, the fact that we hate losing more than we enjoy gaining, making us act quickly to avoid missing out.22

Unity: Humans are wired to seek belonging. In-group bias shows that we naturally favour those who share our identity, whether familial, cultural, or professional. This tendency fosters trust, cooperation, and a sense of collective purpose, aligning our actions with group values.23 Shared goals and experiences create bonds that feel unbreakable, making people more willing to act for the benefit of the group. Unity is the psychological equivalent of a handshake that says, “we’re in this together”. Belonging satisfies the need for connection and security, and people are more likely to help those they perceive as part of their "tribe".

These seven principles rarely act alone, and when combined they create a psychological ripple effect capable of overriding even the most rational minds. Each tactic amplifies the others, reciprocity softens resistance, social proof reduces hesitation, and authority overrides doubt. This layered approach is designed to steer you into an emotional state, making decisions that feel right but are, in truth, irrational.

How to Spot AI Generated Disinformation and Deepfakes

While there are an increasing number of tools that can analyse and flag AI generated media, you may not always have access to them or the expertise to interpret their findings. Therefore, I believe the first line of defence is personal awareness of both the threat and the common weaknesses in AI generated content. Knowing how and why these fakes work may equip you with the mindset to question what you see or hear, even before using technical verification methods. Identifying AI-generated fakes is difficult, and as AI improves, detection gets harder. However, there are several reliable habits and signs that can help.

To make these habits easier to follow, the key strategies for spotting AI-generated disinformation and deepfakes can be grouped into the following core checks:

- Cross-Verify with Credible Sources

- Assess the Source and Context

- Inspect Visuals for Deepfake Clues (Images and Video)

- Be Alert to Audio Anomalies

- Analyse Text Critically

- Use Reverse Image Search and Other Tools

Firstly, always approach surprising or suspicious material with a healthy degree of scepticism, and apply a combination of the following strategies:

Cross-Verify with Credible Sources: If you encounter a dramatic or suspicious claim, image or video online, check whether it has been reported by recognised news outlets or independent fact checkers. Major events should appear in multiple credible sources. If only one obscure account is reporting it, be cautious. Fact checking websites can also reveal whether the claim has already been verified or debunked. A lack of coverage from trusted media, or a claim being flagged as false elsewhere, should raise doubts. News rarely exists in isolation; genuine events are corroborated by multiple witnesses or reports. Pause and verify before accepting or sharing sensational content.

Assess the Source and Context: Look closely at who is sharing the content. Is it from an anonymous or recently created account? Does the account focus only on provocative material? Check its posting history, creation date and level of normal interaction. If the person claims to be an eyewitness, consider whether their profile or past posts make this plausible. For images or videos, think about whether the scene makes sense. Would the person shown likely be in that situation saying or doing those things? If it seems inconsistent or implausible, question its authenticity.24 Disinformation often succeeds because people skip this step, so a brief background check can expose falsehoods.

In Figure 1 above, the images on the right were generated by ChatGPT’s built‑in image generator from those on the left. Context is crucial here. As far as I can verify at the time of this writing, Vladimir Putin and Volodymyr Zelensky only met in person once, at the Normandy Format summit in Paris in 2019.25 Although the summit did include a face‑to‑face meeting, there are no publicly available photos of the two leaders shaking hands or smiling together. That absence alone makes such depictions highly suspect, even before examining their visual authenticity.

Inspect Visuals for Deepfake Clues (Images and Video): An AI-generated photo of Pope Francis wearing a puffer jacket went viral in 2023 before errors in the image were spotted.26 These errors can be seen in Figure 2 below, included an eyelid merging into the frame of his glasses, fingers not actually holding the coffee cup, and a crucifix floating with half its chain missing. Such anomalies can be common in AI images. Look for details that seem unnatural, such as distorted hands or limbs, facial asymmetry, jewellery merging into clothing, or text in the background that appears warped.27 Also check lighting and reflections, if someone is wearing glasses, do the reflections appear viable?28 In busy scenes, the background might contain architectural distortions or repeated patterns unlikely in real photographs.

For deepfake video, many of the same signs apply. Watch for unnatural movements, odd blinking patterns, lip movements that do not match the audio, or sudden glitches around the face.29 Background warping or blurring during head movements can indicate where the AI is merging a synthetic face onto real footage. If possible, find multiple angles of the same event. Even though high quality deepfakes are much harder to spot, remember that careful observation may still reveal inconsistencies.

For live video, asking the person to move an open hand over their face is a quick and worthwhile test, as this may break the deepfake filter.

Be Alert to Audio Anomalies: Voice cloning is becoming increasingly common in social engineering attacks, scams and fake media alike. While it is hard to detect without specialist tools, there are still some common indicators. Listen for unnatural pacing, misplaced emphasis, or tone shifts that do not match the speaker’s usual style.30 Deepfake voices may sound overly formal or have strange pauses. Background noise can be another giveaway, with cloned voices sometimes sounding too clean. Remember, if a caller creates a sense of urgency, end the call and verify their identity and request using official contact details (out of band). Acting immediately without verification is exactly what such attacks and scams rely on.

Analyse Text Critically: Not all disinformation is visual or audio. AI can generate convincing articles, posts or messages. Signs of AI writing include sudden shifts in style, the overuse of emoji’s, repeated points, or sentences that do not logically fit.31 Check for factual errors, overuse of generalities and lack of specific detail. Human writing usually carries a distinct voice or minor imperfections, while AI writing can be overly uniform and impersonal. Furthermore, speed of response can also be flagged as suspicious; extremely fast, well written replies may suggest AI involvement.32 While, fabricated citations are another red flag.33

Use Reverse Image Search and Other Tools: Tools such as Google Images or TinEye can reveal whether a photo has appeared before and in what context.34 This can expose old images being reused to pass off as current events. Reverse searches may also uncover an unaltered version of a manipulated image. Deepfake detection software is improving but remains inconsistent, so no single tool should be relied upon exclusively, as they can produce both false positives and false negatives. Metadata analysis may also reveal editing clues, although this is not foolproof. For critical verification, combining manual checks with tool-based analysis is the most reliable approach.

When combined, these sections create a clear process to help you stay safe and vigilant online.

Staying Safe Online

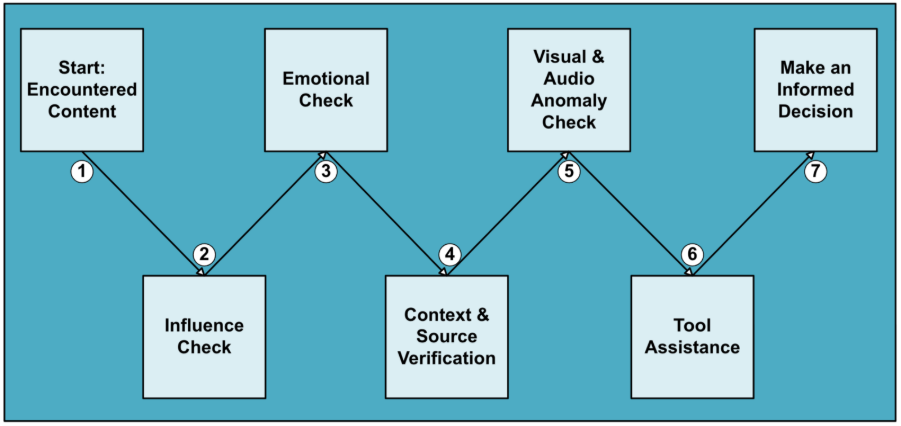

As a culmination of the insights outlined above, the process in Figure 3 below, provides a structured way to strengthen your resistance to online manipulation, reduce the risk of being misled, and make safer, more informed choices. Much like the cyber kill chain maps how an attack unfolds, this framework functions as a defensive chain for individuals, with each step building on the last to interrupt manipulation attempts before they achieve their objective.

1. Encountered Content: The process begins the moment you come across content online

- Pause before reacting or sharing

- Consider all content as “unverified” until “verified”

2. Influence Check: Do you see a combination of the seven principles of influence in play?

- Do I notice authority being invoked?

- Is there an attempt at reciprocity?

- Is scarcity implied?

- Is there social proof?

- Is consistency being pressured?

- Is liking leveraged?

- Is commitment being escalated?

3. Emotional Check: Is this content evoking a strong emotion?

- Am I feeling a strong emotional response?

- Does this content align too perfectly with my existing beliefs or anxieties?

- Am I tempted to reshare immediately without verifying?

- Would I normally question this claim if it were less emotionally charged?

4. Context and Source Verification: Check for context anomalies: unusual claims, missing sources, implausible timing.

- Develop a habit of triangulating information.

- Don’t rely on a single outlet or source, cross-check with at least two independent fact-checker or reputable news organisation.

- See Appendix for some fantastic free online resources to help with this step.

5. Visual and Audio Anomaly Check: Beyond context, do the visuals themselves look consistent and authentic?

- Do faces, hands, or limbs look distorted, asymmetrical, or unnatural?

- Are objects, jewellery, or clothing merging together in ways that don’t seem possible?

- Does the text in the background appear warped, misspelled, or oddly shaped?

- Do lighting, reflections, and shadows line up with the scene realistically?

- In video, do movements, blinking, or lip-syncing look slightly off or mismatched to the audio?

- See Appendix for an oddly addictive free online way to practice this step.

6. Tool Assistance: Apply technical tools to detect manipulation

- Get comfortable using at least one image or video analysis tool.

- See Appendix for some fantastic free online resources to help with this step.

7. Make an Informed Decision: Is the content legitimate? Act accordingly

- Practise restraint.

- Slowing down and withholding engagement can be one of the most effective defences against misinformation.

Conclusion

This piece has shown that AI-generated disinformation and deepfakes are effective not only because of advancing technology but because they exploit the oldest weaknesses in human nature. The seven principles of influence demonstrate how and why people can be pushed into irrational decisions, and research has proven that most of us are far less capable of spotting manipulation and deepfakes than we believe. To close that gap, the process outlined here provides a practical framework for slowing down reactions, breaking the emotional pull of deceptive content, and replacing instinct with deliberate checks. The process offers a structured way to push back, with each step strengthening the next and creating a rhythm that builds resilience where instinct alone so often fails.

However, it is important to avoid becoming so sceptical that genuine events are dismissed as false. The aim is to strike a balance by being cautious and analytical without becoming paralysed. Just as in cybersecurity, where systems tuned too tightly may generate a flood of false positives that could cause fatigue and real threats to be missed, excessive scepticism can blind us to genuine information. Balance is key: stay alert, not alarmed. To end, remember that awareness and education remain among the most effective defences against these attacks and deceptions, just as with traditional social engineering threats where training people to recognise influence is critical.

References

1 eSafety Commissioner (Australia), “Deepfake Trends & Challenges,” published May 28, 2025, accessed August 14, 2025, https://www.esafety.gov.au/industry/tech-trends-and-challenges/deepfakes.

2 Australian Cyber Security Centre, Annual Cyber Threat Report 2023–2024, published November 20, 2024, accessed August 14, 2025, https://www.cyber.gov.au/about-us/view-all-content/reports-and-statistics/annual-cyber-threat-report-2023-2024.

3 Australian Cyber Security Centre, Annual Cyber Threat Report 2023–2024.

4 KPMG, Deepfake: How Real Is It?, published May 2025, accessed August 14, 2025, https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmgsites/in/pdf/2024/12/deepfake-how-real-is-it.pdf.

5 “Misinformation vs. Disinformation: Get Informed on the Difference,” Dictionary.com, published August 15, 2022, accessed August 19, 2025, https://www.dictionary.com/e/misinformation-vs-disinformation-get-informed-on-the-difference/.

6 “Misinformation and Disinformation,” Encyclopædia Britannica, last updated July 27, 2025, accessed August 19, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/topic/misinformation-and-disinformation.

7 Victoria Police, “Deepfakes | Your Safety,” published June 26, 2025, accessed August 14, 2025, https://www.police.vic.gov.au/deepfakes.

8 eSafety Commissioner (Australia), “Deepfake Trends & Challenges.”

9 “CDC Report on Human Deepfake Detection,” published December 2024, accessed August 14, 2025, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2451958824001714.

10 Robert Greene, The Laws of Human Nature (New York: Viking, 2018), P 22 – 52.

11 “Finance Worker Transfers £20m to Criminals After Being Caught in ‘Deepfake’ Scam,” Association of International Accountants (AIA), published December 13, 2024, accessed August 14, 2025, https://www.aiaworldwide.com/news/accounting-and-finance-news/finance-worker-transfers-20m-to-criminals-after-being-caught-in-deepfake-scam/.

12 Sean Hughes, Ohad Fried, Melissa Ferguson, Ciaran Hughes, Rian Hughes, Xinwei Yao, and Ian Hussey, “Deepfaked Online Content Is Highly Effective in Manipulating People’s Attitudes and Intentions,” published March 7, 2021, accessed August 19, 2025, https://lss.fnal.gov/archive/2021/pub/fermilab-pub-21-182-t.pdf.

13 Bobby Chesney and Danielle Citron, “Deep Fakes: A Looming Challenge for Privacy, Democracy, and National Security,” California Law Review, published December 2019, https://www.californialawreview.org/print/deep-fakes-a-looming-challenge-for-privacy-democracy-and-national-security.

14 Robert B. Cialdini, Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion (New York: Harper Business, 2006).

15 Robert B. Cialdini, Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion (New York: Harper Business, 2006), p 24 – 26.

16 Saul McLeod, PhD, “What Is Cognitive Dissonance Theory?,” Simply Psychology, last updated June 20, 2025, accessed August 20, 2025, https://www.simplypsychology.org/cognitive-dissonance.html.

17 Saul McLeod, “Bandura—Social Learning Theory,” Simply Psychology, published 2011, accessed August 20, 2025, https://www.simplypsychology.org/bandura.html.

18 Saul McLeod, PhD, “Stanley Milgram Shock Experiment,” Simply Psychology, last updated March 14, 2025, accessed August 20, 2025, https://www.simplypsychology.org/milgram.html.

19 Joshua Loo, “Similarity Hypothesis,” The Decision Lab, accessed August 20, 2025, https://thedecisionlab.com/reference-guide/sociology/similarity-hypothesis.

20 Ayesh Perera, “Halo Effect in Psychology: Definition & Examples,” Simply Psychology, last updated September 7, 2023, accessed August 20, 2025, https://www.simplypsychology.org/halo-effect.html;

21 “Reactance Theory,” The Decision Lab, accessed August 20, 2025, https://thedecisionlab.com/reference-guide/psychology/reactance-theory.

22 “Loss Aversion,” The Decision Lab, accessed August 20, 2025, https://thedecisionlab.com/biases/loss-aversion.

23 “In-Group Bias,” The Decision Lab, accessed August 20, 2025, https://thedecisionlab.com/biases/in-group-bias.

24 Australian Cyber Security Centre, “Spotting Scams,” published August 20, 2024, accessed August 14, 2025, https://www.cyber.gov.au/protect-yourself/spotting-scams.

25 “Zelensky and Putin in Paris: What Is Success?,” Center for Strategic & International Studies, published December 6, 2019, accessed August 19, 2025, https://www.csis.org/analysis/zelensky-and-putin-paris-what-success.

26 “Fake Photos of Pope Francis in a Puffer Jacket,” CBS News, published March 28, 2023, accessed August 14, 2025, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/pope-francis-puffer-jacket-fake-photos-deepfake-power-peril-of-ai/.

27 “Fake Photos of Pope Francis in a Puffer Jacket,” CBS News.

28 Australian Cyber Security Centre, “Spotting Scams.”

29 Ibid.

30 “How to Spot AI Audio Deepfakes at Election Time,” McAfee, published April 22, 2023, accessed August 14, 2025, https://www.mcafee.com/blogs/internet-security/how-to-spot-ai-audio-deepfakes-at-election-time/.

31 “Detecting AI-Generated Text: Things to Watch For,” East Central College, published February 17, 2023, accessed August 14, 2025, https://www.eastcentral.edu/free/ai-faculty-resources/detecting-ai-generated-text/.

32 “Detecting AI-Generated Text: Things to Watch For,” East Central College.

33 Ibid.

34 “TinEye,” accessed August 14, 2025, https://tineye.com/.

More Resources for Detecting AI Disinformation

Influence Check

For a more detailed explanation, see Influence at Work: The 7 Principles of Persuasion. https://www.influenceatwork.com/7-principles-of-persuasion/

Context and Source Verification

Here are some fantastic free online resources to help with this step:

Independent Fact-Checking Resources:

- PolitiFact: Political and policy-related claims. https://www.politifact.com/

- Full Fact: UK-focused fact-checking. https://fullfact.org/

- Snopes: General fact checks, urban legends, hoaxes. https://www.snopes.com/

Reverse Image Search Tools:

- TinEye: Detect reused or manipulated images. https://tineye.com/

- Google Reverse Image Search: Identify origins of images. https://www.google.com/imghp

Visual and Audio Anomaly Check

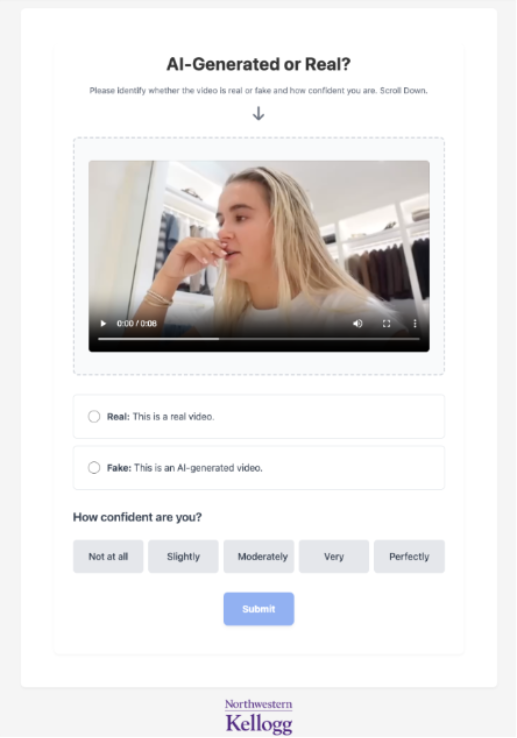

If you fancy testing how sharp your deepfake spotting instincts are, try out the free ‘Detect Fakes’ game, created by researchers at Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management. You might find it oddly addictive. https://detectfakes.kellogg.northwestern.edu/

This was my score after 10 videos in Figure 5 below, can you beat it?

Tool Assistance

Here are a few free and accessible tools can help uncover tampering:

- ExifTool: Metadata analysis that can reveal signs of editing or manipulation. https://exiftool.org/

- Forensically: A web-based tool for detecting image anomalies such as cloning or compression artefacts. https://29a.ch/photo-forensics/#forensic-magnifier

- Undetectable.ai: AI-Image Detector, Useful for flagging content that may have been generated or altered by artificial intelligence. https://undetectable.ai/ai-image-detector

- InVID & WeVerify: Browser extensions widely used by journalists for video verification. https://weverify.eu/# https://www.invid-project.eu/

FEATURED RESOURCES

Anomali Cyber Watch: LockBit 5.0, Chrome Zero-Day CVE-2026-2441, Infostealer Targets OpenClaw, and more

Anomali Cyber Watch: Zero-Click Affects Claude, SolarWinds Vulnerabilities for Velociraptor and more